Complete History of the Musée Rodin

From Auguste Rodin’s studio spirit to a museum in dialogue with light, nature, and time.

Table of Contents

Auguste Rodin: Life & Legacy

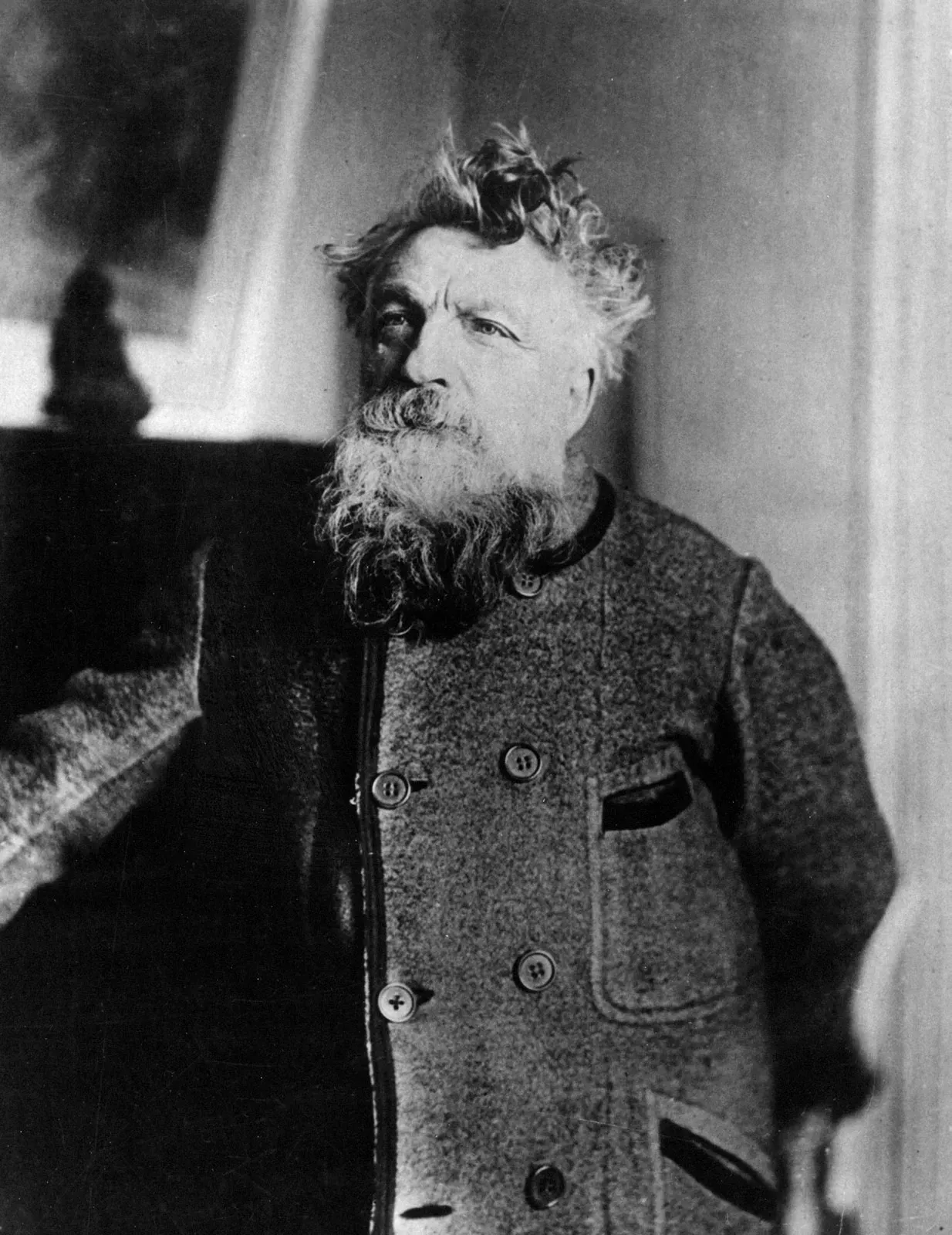

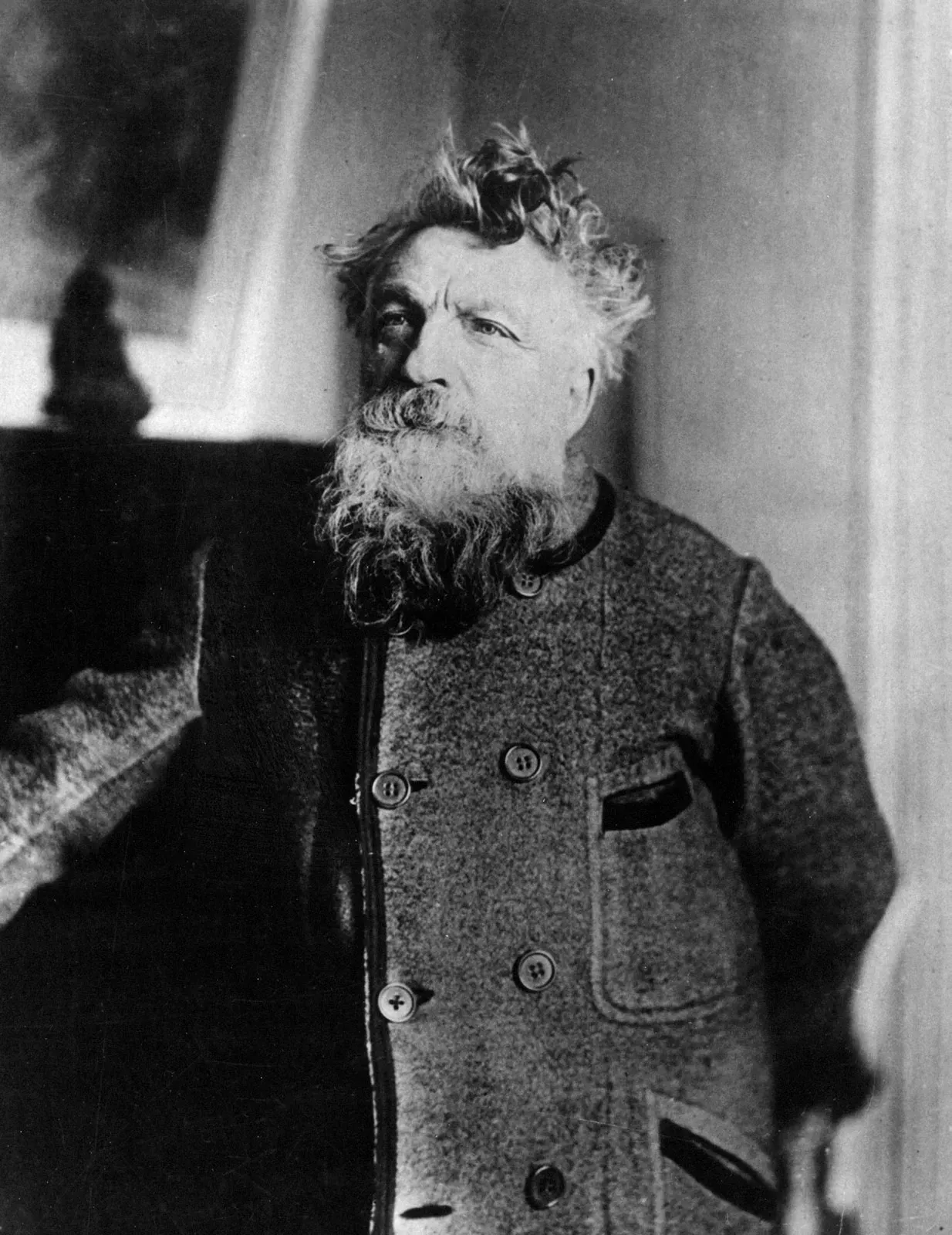

Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) pursued sculpture with an intensity that made material feel alive. His figures breathe, strain, hesitate — as if caught mid-thought, mid-motion. After years of rejection, he forged a language of broken surfaces and recomposed bodies that unsettled academic taste yet spoke powerfully to modern life. Success brought commissions and controversy: a sensuous Kiss, a brooding Thinker, and the vast, seething ensemble of The Gates of Hell.

Late in life, Rodin envisioned an enduring home for his art. In 1916, he donated his works, collections, archives, and copyrights to the French state on the condition that a museum be created at the Hôtel Biron. It was more than a legacy; it was a blueprint for how to encounter sculpture — with time, with light, with the human body’s capacity for empathy.

Hôtel Biron: A House Becomes a Museum

Built in the 18th century, the Hôtel Biron drifted through uses before becoming a haven for artists in the early 1900s. Rodin rented rooms here; so did poets and painters, finding inspiration in the generous windows, parquet floors, and the surrounding garden that muffles the city’s noise.

The state accepted Rodin’s 1916 gift, and in 1919 the museum opened. Over time, careful restorations preserved the mansion’s luminous character while improving conservation. Today, it feels both domestic and ceremonial — a salon for sculpture, an intimate stage for bronze and marble.

From Studio to Garden: Display Philosophy

The museum’s philosophy echoes the studio: show process alongside masterpiece. Plasters, multiple states, and fragmentary hands sit near finished marbles. Outside, bronzes meet wind and weather — surfaces gather light, and shadows shift with every passing cloud.

This blend of inside and outside is deliberate. Sculpture here is not just seen but felt in space and time — textures warming in sun, contours cooled by shade, and the visitor’s path becoming part of the artwork’s unfolding.

Masterworks: Thinker, Kiss & Gates

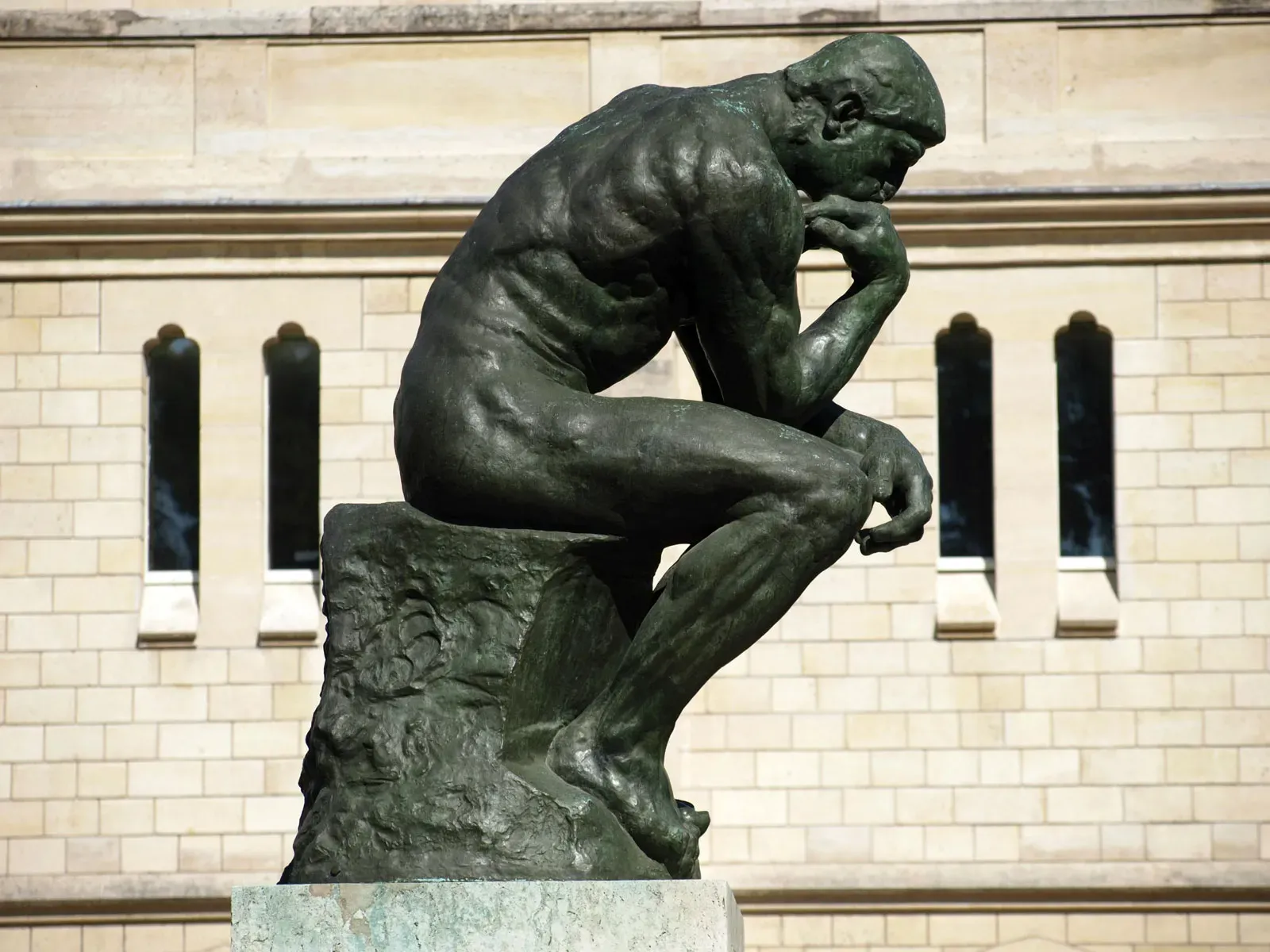

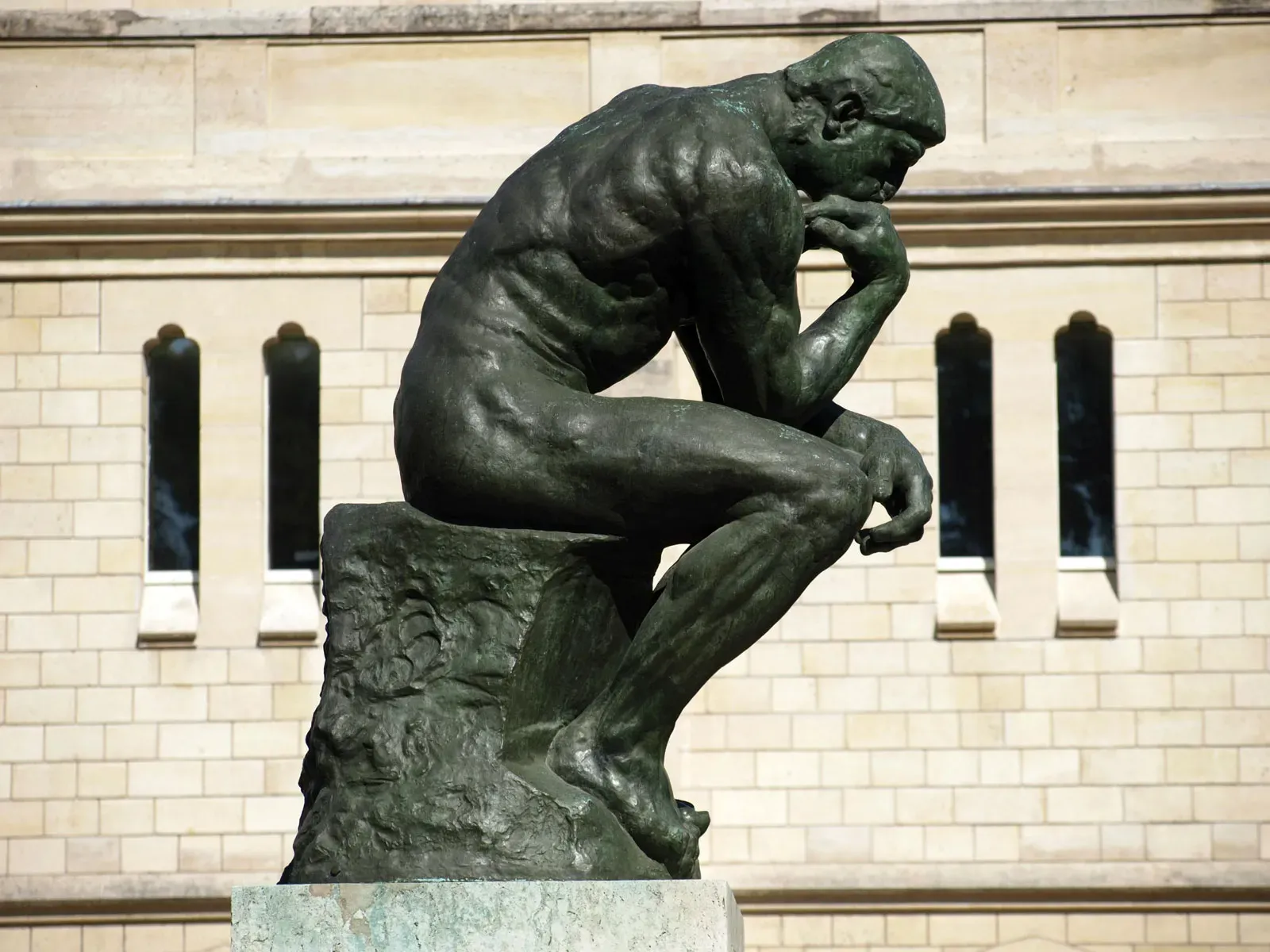

Few ensembles are as magnetic as The Gates of Hell, a portal dense with figures dreaming, falling, and turning upon themselves. Nearby, The Thinker gathers tension in every muscle, a mind’s weight rendered in bronze. The Kiss, by contrast, quiets the room: two bodies at once ideal and human, tender and monumental.

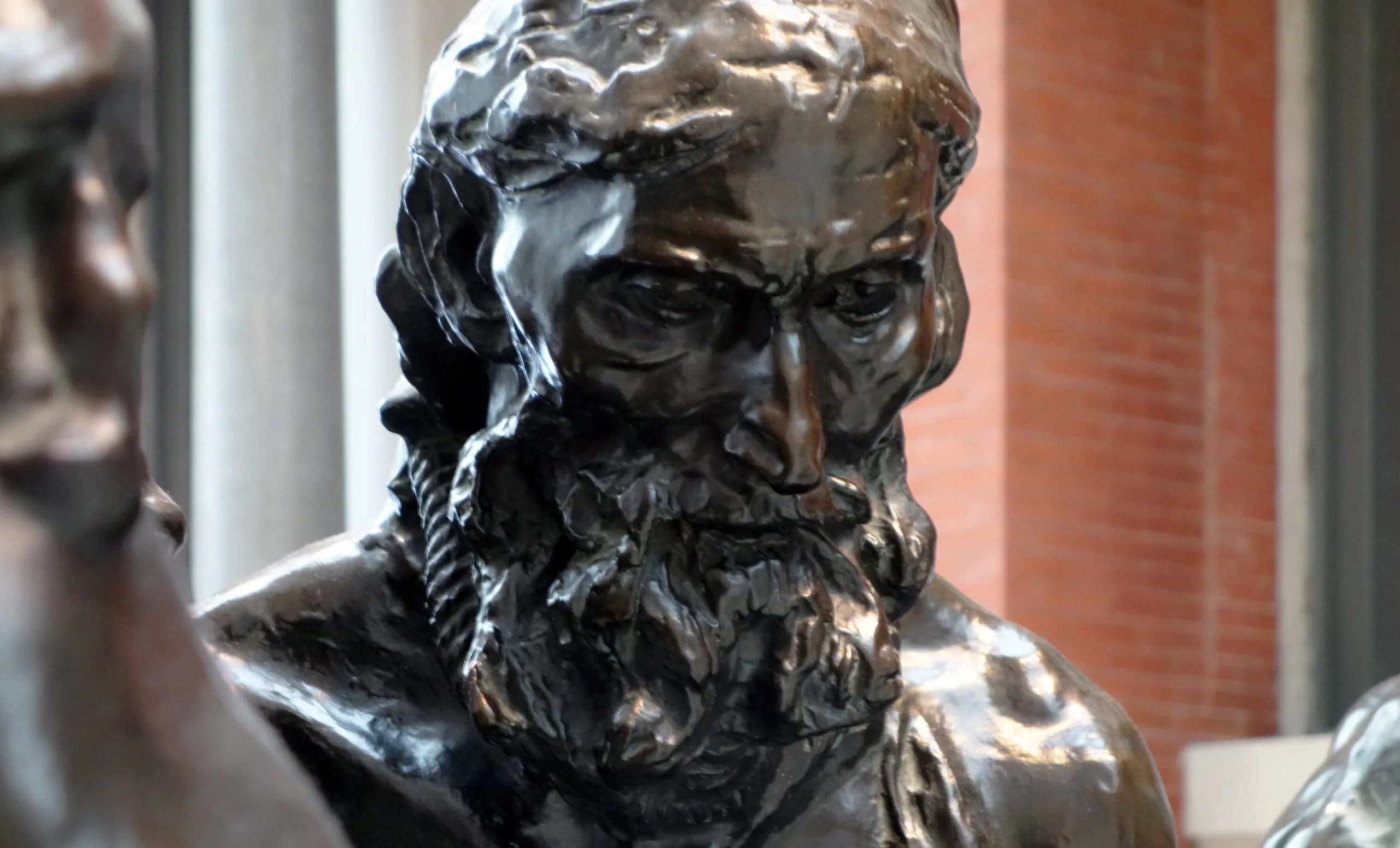

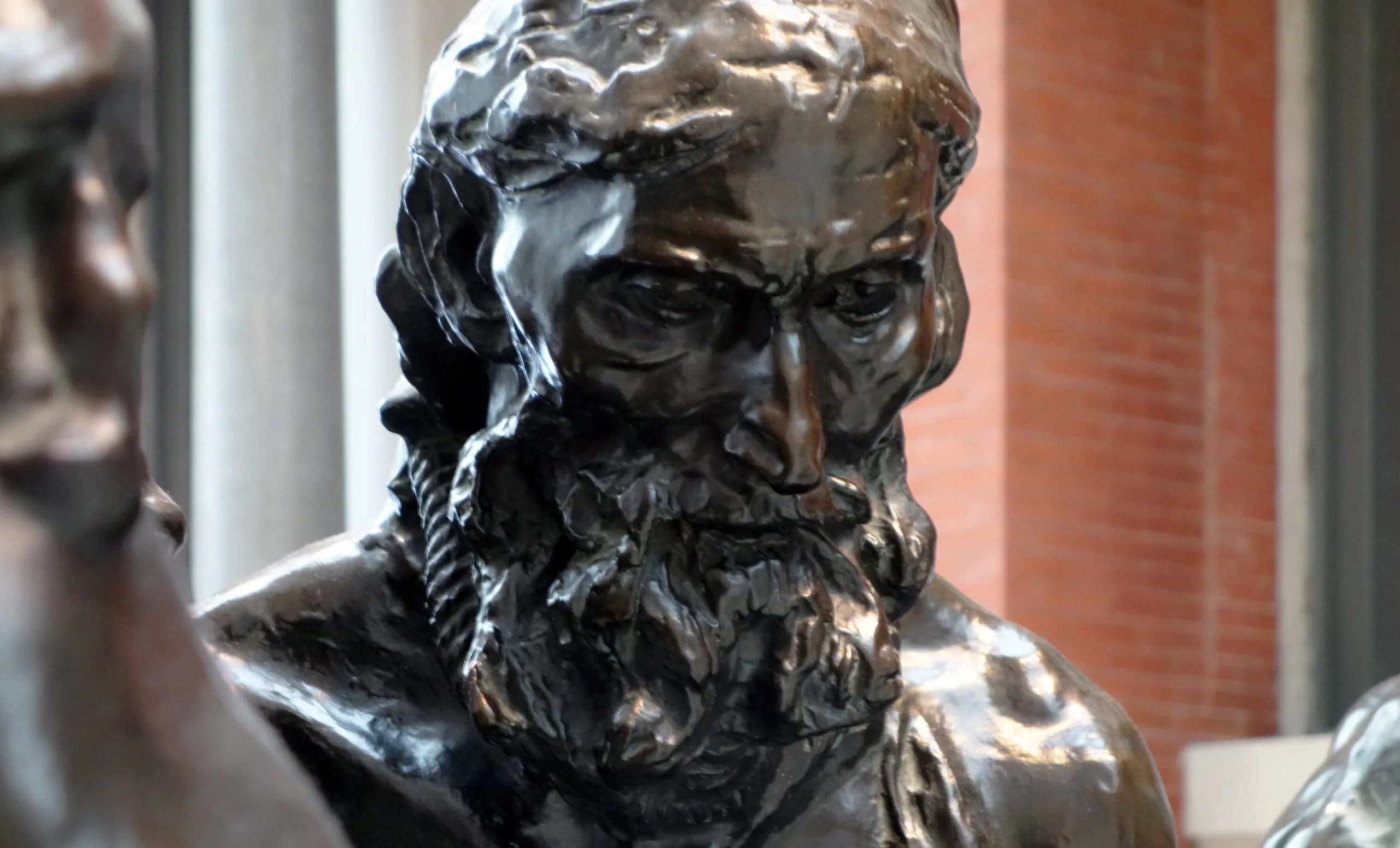

Around these works orbit portraits and monuments — the Burghers of Calais, the Monument to Balzac — that show Rodin’s empathy for presence. His subjects are not posed; they arrive, with gravity and flaw and dignity intact.

Camille Claudel: Dialogue & Distance

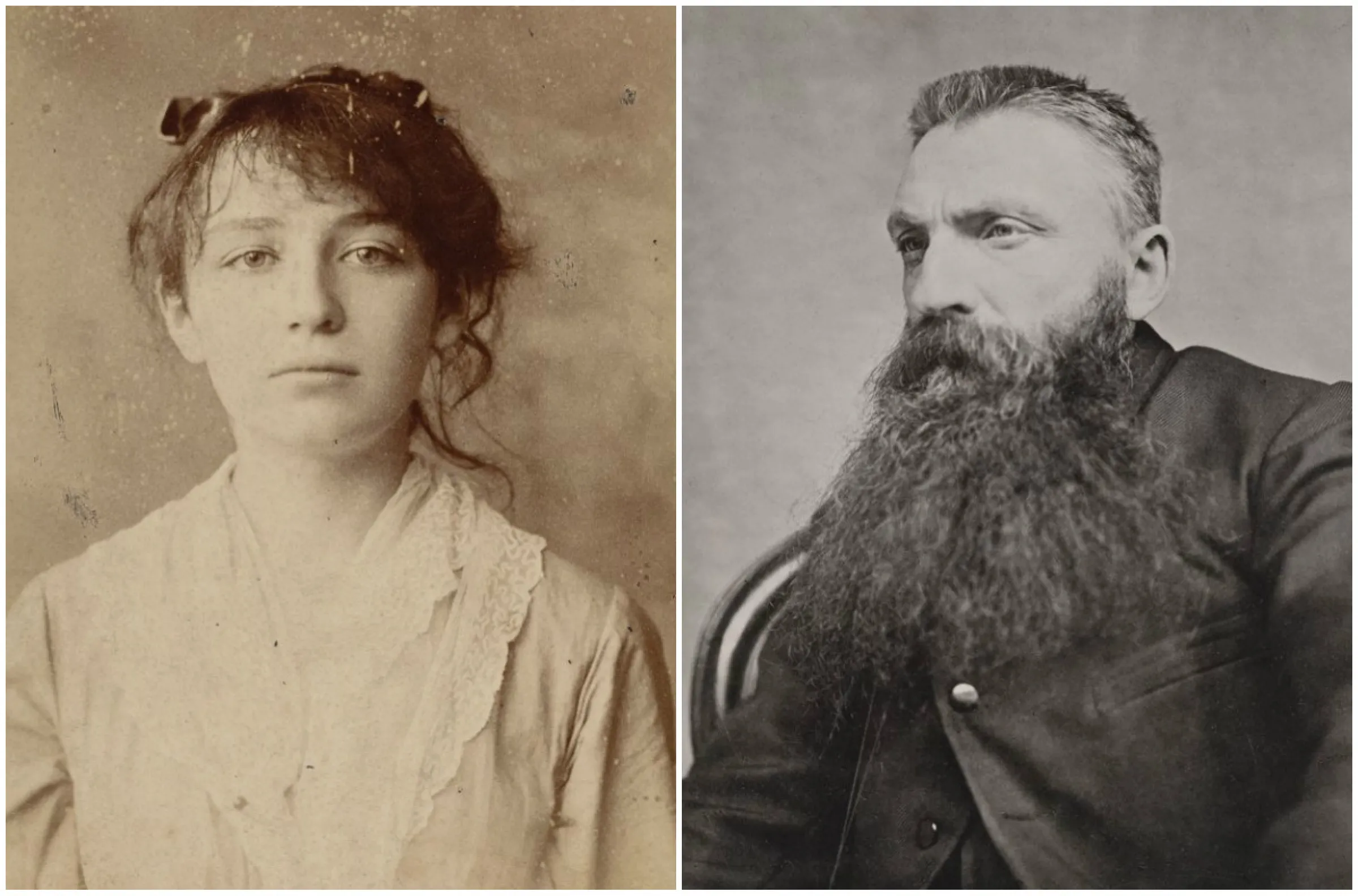

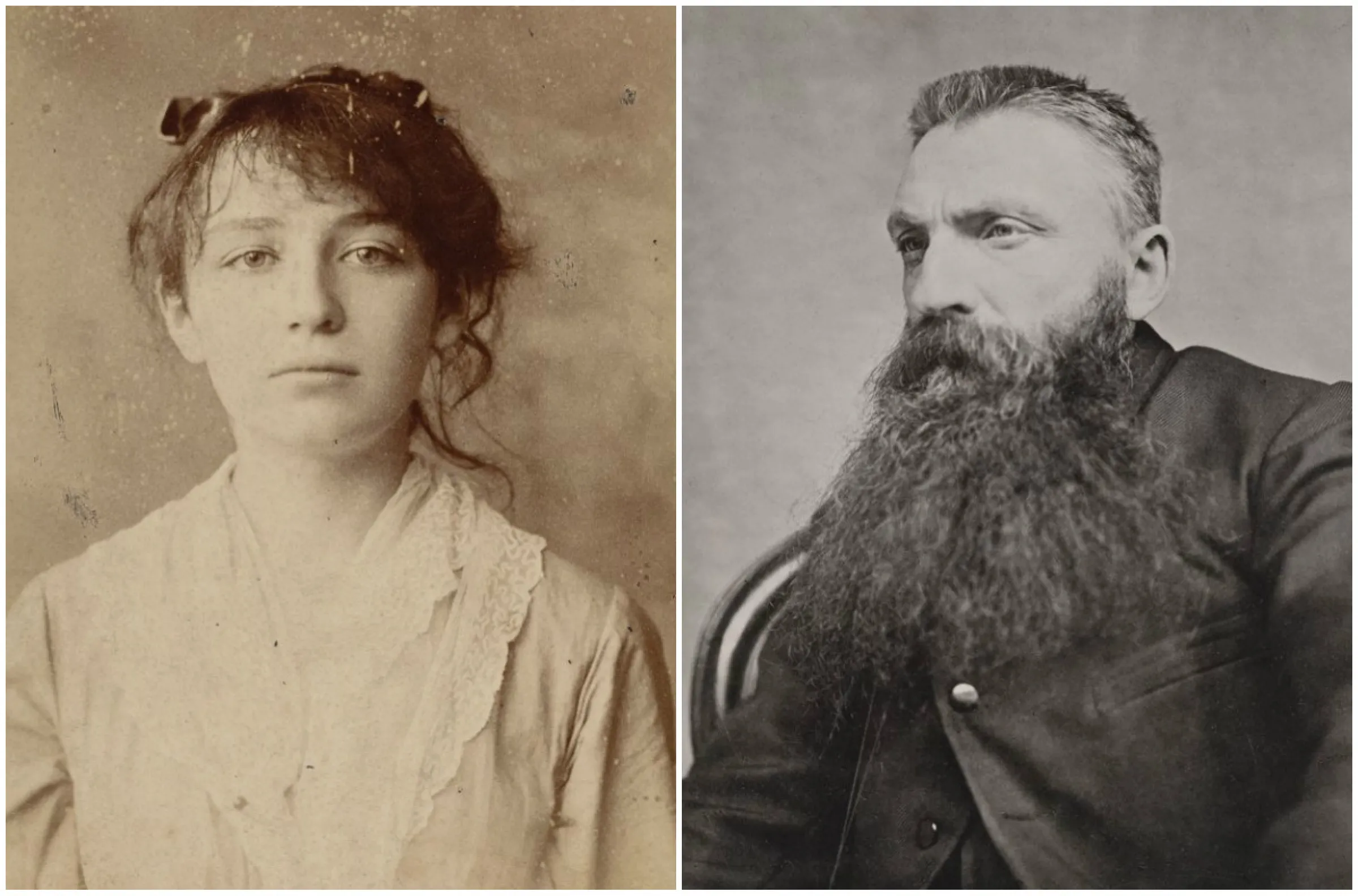

Camille Claudel (1864–1943) stands beside Rodin as an artist of fierce originality. Their years of collaboration were charged — professionally, emotionally, artistically — and her sculptures convey a different lightness and psychological acuity: hair swept by motion, drapery alive to the body’s undercurrent.

The museum acknowledges this shared, complex history by presenting Claudel’s works in conversation with Rodin’s. That dialogue widens our sense of the period and reframes who shapes an artist’s ‘genius’.

Casting, Plasters & Authenticity

Rodin authorized multiple casts of certain bronzes; many were completed posthumously within strict limits. Foundry marks, editions, and patinas become part of the story — not a diminishment, but a record of how sculpture circulates and how an idea inhabits material.

Plasters, too, carry authority. They show changes of mind, the energy of working hands, and the scaffolding beneath a famous pose. To stand before a plaster is to watch thinking made visible.

Visitors, Education & Changing Displays

Exhibitions rotate, new research emerges, and the museum adapts displays to reveal unexpected connections — between portraits and fragments, between ancient forms and modern gesture. Audio guides and programs invite slow looking and lively conversation.

Families trace shapes in the garden; students sketch hands and torsos; seasoned visitors return for the way afternoon light softens a bronze. The museum grows not by adding noise, but by refining attention.

The Museum in Wartime

Through the upheavals of the 20th century, the Hôtel Biron and its collections required vigilance and care. Wartime years brought constraints, protections, and the quiet work of safeguarding plasters, marbles, and archives.

What endures is the conviction that art anchors memory. The museum’s postwar life reaffirmed its mission: to keep Rodin’s works present, studied, and accessible to a public reshaped by history.

Rodin in Popular Culture

From postcards to cinema, Rodin’s silhouettes — the bowed head of The Thinker, the entwined figures of The Kiss — have become part of visual culture, shorthand for thought and touch.

Artists, designers, and filmmakers borrow these forms to ask new questions about the body and emotion. The museum, in turn, offers the originals’ quiet authority.

Visiting Today

A visit moves between garden and mansion. Paths open to vistas, rooms concentrate attention. Benches invite pauses; windows frame a bronze against trees — a living backdrop that changes by hour and season.

Practical improvements — climate control, lighting, accessibility measures — support the art without breaking the spell of place. It still feels like an artist’s domain, shared generously with the city.

Conservation & Future Plans

Sculpture requires care: patinas refreshed, surfaces cleaned, internal structures checked. Conservation teams balance stability with respect for historic finishes and tool marks.

Future plans continue this stewardship — deepening research access, refining displays, and sustaining the garden so that light and leaf keep conversing with bronze.

Nearby Paris Landmarks

Les Invalides lies just next door; the Musée d’Orsay is a pleasant walk across the Seine. Farther west, the Eiffel Tower offers a grand counterpoint to the garden’s intimacy.

After your visit, linger in the neighborhood’s cafés and bookstores — it’s a corner of Paris that rewards unhurried afternoons.

Cultural & National Significance

The Musée Rodin is more than a collection; it’s a national testament to how an artist’s gift can shape public life — inviting reflection, care, and the simple joy of looking.

Here, sculpture meets the weather, and the city finds a moment’s repose. That balance — between intensity and calm — is the museum’s quiet promise to every visitor.

Table of Contents

Auguste Rodin: Life & Legacy

Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) pursued sculpture with an intensity that made material feel alive. His figures breathe, strain, hesitate — as if caught mid-thought, mid-motion. After years of rejection, he forged a language of broken surfaces and recomposed bodies that unsettled academic taste yet spoke powerfully to modern life. Success brought commissions and controversy: a sensuous Kiss, a brooding Thinker, and the vast, seething ensemble of The Gates of Hell.

Late in life, Rodin envisioned an enduring home for his art. In 1916, he donated his works, collections, archives, and copyrights to the French state on the condition that a museum be created at the Hôtel Biron. It was more than a legacy; it was a blueprint for how to encounter sculpture — with time, with light, with the human body’s capacity for empathy.

Hôtel Biron: A House Becomes a Museum

Built in the 18th century, the Hôtel Biron drifted through uses before becoming a haven for artists in the early 1900s. Rodin rented rooms here; so did poets and painters, finding inspiration in the generous windows, parquet floors, and the surrounding garden that muffles the city’s noise.

The state accepted Rodin’s 1916 gift, and in 1919 the museum opened. Over time, careful restorations preserved the mansion’s luminous character while improving conservation. Today, it feels both domestic and ceremonial — a salon for sculpture, an intimate stage for bronze and marble.

From Studio to Garden: Display Philosophy

The museum’s philosophy echoes the studio: show process alongside masterpiece. Plasters, multiple states, and fragmentary hands sit near finished marbles. Outside, bronzes meet wind and weather — surfaces gather light, and shadows shift with every passing cloud.

This blend of inside and outside is deliberate. Sculpture here is not just seen but felt in space and time — textures warming in sun, contours cooled by shade, and the visitor’s path becoming part of the artwork’s unfolding.

Masterworks: Thinker, Kiss & Gates

Few ensembles are as magnetic as The Gates of Hell, a portal dense with figures dreaming, falling, and turning upon themselves. Nearby, The Thinker gathers tension in every muscle, a mind’s weight rendered in bronze. The Kiss, by contrast, quiets the room: two bodies at once ideal and human, tender and monumental.

Around these works orbit portraits and monuments — the Burghers of Calais, the Monument to Balzac — that show Rodin’s empathy for presence. His subjects are not posed; they arrive, with gravity and flaw and dignity intact.

Camille Claudel: Dialogue & Distance

Camille Claudel (1864–1943) stands beside Rodin as an artist of fierce originality. Their years of collaboration were charged — professionally, emotionally, artistically — and her sculptures convey a different lightness and psychological acuity: hair swept by motion, drapery alive to the body’s undercurrent.

The museum acknowledges this shared, complex history by presenting Claudel’s works in conversation with Rodin’s. That dialogue widens our sense of the period and reframes who shapes an artist’s ‘genius’.

Casting, Plasters & Authenticity

Rodin authorized multiple casts of certain bronzes; many were completed posthumously within strict limits. Foundry marks, editions, and patinas become part of the story — not a diminishment, but a record of how sculpture circulates and how an idea inhabits material.

Plasters, too, carry authority. They show changes of mind, the energy of working hands, and the scaffolding beneath a famous pose. To stand before a plaster is to watch thinking made visible.

Visitors, Education & Changing Displays

Exhibitions rotate, new research emerges, and the museum adapts displays to reveal unexpected connections — between portraits and fragments, between ancient forms and modern gesture. Audio guides and programs invite slow looking and lively conversation.

Families trace shapes in the garden; students sketch hands and torsos; seasoned visitors return for the way afternoon light softens a bronze. The museum grows not by adding noise, but by refining attention.

The Museum in Wartime

Through the upheavals of the 20th century, the Hôtel Biron and its collections required vigilance and care. Wartime years brought constraints, protections, and the quiet work of safeguarding plasters, marbles, and archives.

What endures is the conviction that art anchors memory. The museum’s postwar life reaffirmed its mission: to keep Rodin’s works present, studied, and accessible to a public reshaped by history.

Rodin in Popular Culture

From postcards to cinema, Rodin’s silhouettes — the bowed head of The Thinker, the entwined figures of The Kiss — have become part of visual culture, shorthand for thought and touch.

Artists, designers, and filmmakers borrow these forms to ask new questions about the body and emotion. The museum, in turn, offers the originals’ quiet authority.

Visiting Today

A visit moves between garden and mansion. Paths open to vistas, rooms concentrate attention. Benches invite pauses; windows frame a bronze against trees — a living backdrop that changes by hour and season.

Practical improvements — climate control, lighting, accessibility measures — support the art without breaking the spell of place. It still feels like an artist’s domain, shared generously with the city.

Conservation & Future Plans

Sculpture requires care: patinas refreshed, surfaces cleaned, internal structures checked. Conservation teams balance stability with respect for historic finishes and tool marks.

Future plans continue this stewardship — deepening research access, refining displays, and sustaining the garden so that light and leaf keep conversing with bronze.

Nearby Paris Landmarks

Les Invalides lies just next door; the Musée d’Orsay is a pleasant walk across the Seine. Farther west, the Eiffel Tower offers a grand counterpoint to the garden’s intimacy.

After your visit, linger in the neighborhood’s cafés and bookstores — it’s a corner of Paris that rewards unhurried afternoons.

Cultural & National Significance

The Musée Rodin is more than a collection; it’s a national testament to how an artist’s gift can shape public life — inviting reflection, care, and the simple joy of looking.

Here, sculpture meets the weather, and the city finds a moment’s repose. That balance — between intensity and calm — is the museum’s quiet promise to every visitor.